Archiving: Great sailing related article on reefing sails

Posted By RichC on December 30, 2016

There are much better places to save articles than a publicly available blog like Evernote, GetPocket, Google apps as well as locally archived HTML, Docs and PDFs, but I still occasionally enjoy having them on MyDesultoryBlog. So as with a few other archived articles on reefing (1 & 2), I’m saving this Cruising World Seamanship 101: Reefing the Main article on myarchive (also testing a larger slideshow WordPress plugin for images at the bottom of the post — hold cursor over the slideshow image to pause).

Seamanship 101: Reefing the Main

Mastering this basic tenet of seamanship can help any sailor control the circumstances when the conditions get gnarly.

A few years back, on a gusty day with winds over 40 knots, my 34-year-old Cape Dory 28, Nikki — a cruising boat I live aboard — won the coveted Michelob Cup on Florida’s Tampa Bay, topping a fleet of more than 40 other yachts, most of which were hard-core raceboats. Not coincidentally, Nikki’s crew had trained in heavy weather and could reef the mainsail in 40 seconds or less, and shake it out even quicker.

Nobody in Tampa Bay racing circles had ever seen or competed against Nikki. She was the oldest and smallest boat to race that day. Though we were later accused of cheating by a disgruntled opponent (and quickly exonerated), Nikki continued her winning ways and was later named Southwest Florida’s Cruising Boat of the Year by the West Florida PHRF Racing Association. Proficient and rapid reefing remained a key to our success. In fact, unlike many of our competitors, we always hoped for strong winds on race days.

Of course, there are lots of reasons to reef that are more important than winning races. Well-executed, timely reefing has a positive impact on your boat’s performance and safety in heavy weather. A well-balanced sail plan also keeps your crew and passengers safer and able to move about more comfortably, increasing their level of confidence in your sailing abilities and attention to their welfare. There’s nothing that will ruin a day on the water faster than a partner or friend screaming, “We’re tipping over!”

Here are a few more ways reefing promotes better sailing:

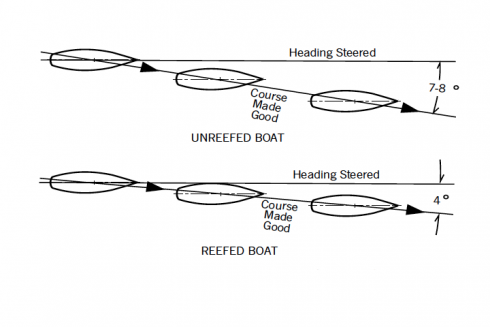

- Keeps the boat “on its feet” and more efficient in terms of hydrodynamics and aerodynamics.

- Increases speed potential in rough conditions.

- Reduces adverse weather helm (unnecessary drag).

- Dramatically reduces leeway when pointing and close-reaching.

- Reduces wear and tear on sails and equipment.

- Makes sails easier to trim and handle.

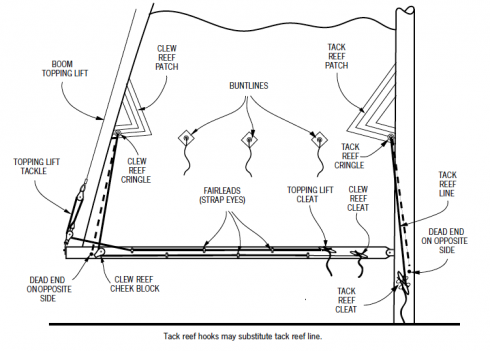

- Setup and Sequences

It’s important that all the hardware and running rigging for reefing maneuvers are close at hand. For a classic plastic cruiser like Nikki, the reefing-control gear — the bitter ends of the reefing tack and clew lines and their respective cleats or clutches — should be situated on the same side of the mast and/or boom as the main halyard winch (usually on the starboard side). On more contemporary cruising boats, this gear is often led aft to the coachroof, flanking the companionway. The main topping lift should also be readily close by. This way, the crew tucking in the reef needn’t move from one side of the boat to the other to complete the task. Topping lifts and clew lines should never terminate at or near the end of the boom; these would potentially require the crew to hang dangerously over the lifelines to access them.

Because they’re quickly made, saving valuable time, I prefer cam or clam cleats for all reefing control lines. On the boom, reefing clew lines are best installed internally to keep the spar uncluttered. Alternatively, these clew lines can be routed through three or four small strapeyes that are machine-screwed to the boom.

Many booms are equipped with reefing tack hooks integral with the gooseneck; others have dedicated tack lines. Nikki has both, and I’ve found that the tack line is much faster to use, saving precious seconds.

Whether you sail a sloop, cutter, yawl or ketch, the traditional jiffy- or slab-reefing sequence is virtually universal. Practice it with your crew until reefing becomes a streamlined and habitual process. Eliminate confusion, yelling and mistakes. The job should be smooth and rapid. The following is the correct sequence for all boats that do not employ a single-line system (more on those in a moment). On Nikki I’ve actually printed out and laminated two copies of these instructions, and taped one to the mast and the other in the cockpit.

Here’s the drill:

- Ease the boom vang and then the mainsheet so both are slack.

- Take up the topping lift so the boom is stabilized.

- Lower the main halyard until the desired reefing tack cringle is in position.

- Tighten and make fast the reefing tack line, or put the tack cringle onto the gooseneck hook, ring or shackle.

- Hoist the main halyard until the luff is firm and wrinkle-free.

- Take in the reefing clew line, or luff cringle, via a boom winch or tackle as much as possible, and make fast.

- Ease the main topping lift.

- Trim the mainsheet.

- Tighten the boom vang.

Personally, I find this slab-reefing system, with separate controls for the leech and luff of the sail, to be preferable to single-line reefing systems. First, due to the friction and loads caused by a single-line system running through multiple sheaves and leads before terminating in the cockpit, those sheaves are not timesavers. Also, because the reefing line is so long, it may develop kinks in the line that delay the maneuver until they’re straightened out. Finally, single-line reefs eliminate the ability to adjust sail draft and leech tension separately.

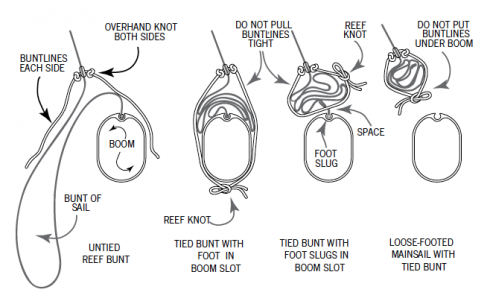

So now that your sail is reefed, what do you do with the lowered panels of the sail that are no longer set? On Nikki, I use dedicated buntlines: small-diameter lengths of line that pass through a horizontal series of cringles in the sail, between the reefed tack and the reefed clew, and tied with reef knots. Their only purpose is to store the “bunt” — that excess sailcloth that hangs down from the finished reef — to increase visibility from the helm and reduce flopping. For mainsails without buntlines, the sail can be gathered and secured with sail ties rove through the appropriate reef points, or through cringles in the sail, which serve the same purpose. Either way, buntlines or sail ties should never be pulled tight before tying, because they will strain and eventually tear the sail at the cringles. Your reefed sail should be left loose-footed, although the buntlines or ties can be knotted under the boom or only around the bunt itself, which I prefer. When I race Nikki, I leave the bunt untied because it doesn’t get in the way and it reduces the time to take another reef in or shake it out.

Over the years, I’ve heard some sailors say they don’t know how or when to reef, justifying this confession by stating that they don’t sail when it’s too breezy, or they simply bear away as the wind stiffens. This is shortsighted and even dangerous, for the day will come when you’re caught in a rising squall or changing weather, and there are few choices or tactics other than reducing sail.

So practice with your family and regular crewmembers, and you’ll soon discover how easy reefing really is. Keep a stopwatch handy and try to beat your best time. This skill will broaden your sailing horizons and increase your self-reliance dramatically as you discover what you and your boat are capable of when conditions deteriorate.

Learning to reef quickly will also teach you what needs to be corrected or modified on your boat to make reefing more effective and convenient. Boat manufacturers are not necessarily heavy-weather sailors and often take shortcuts. What they install is not always ideal in terms of hardware or deck layouts.

In my experience, sailmakers, mast and boom assemblers, and yacht designers aren’t always on the same page either, and the result can be reefing systems that just don’t work.

So let’s delve a bit deeper and focus on some of the finer points of the design and installation of reefing hardware.

End-Boom Dilemmas

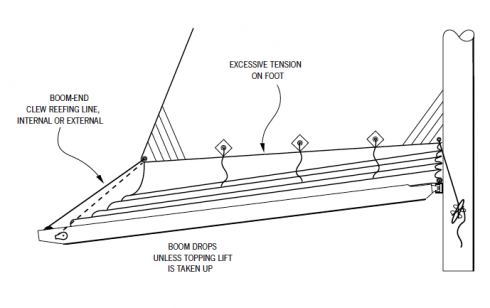

If you have a boom with an internal reefing system — with sheaves for the clew(s) installed at the outboard end of the boom — you’ve probably ascertained that something wasn’t right when you tried to set a reef. Most likely, your boom drooped to an odd angle and may even have ended up on top of your bimini or dodger. If your boom has external clew reef lines with cheek blocks and dead-end padeyes installed at the end of the boom, the same thing will happen.

To make matters worse, if the clew reef lines are led to cleats that are also near the end of the boom, you can’t reach them unless you are either sheeted in and sailing to weather or luffing head to wind.

Clew reefing lines emanating from the end of the boom are not only inefficient; they can be hazardous for anyone who has to make them up while hanging over a lifeline or under a thrashing boom.

In other words, there’s really no excuse for this system on a well-found cruising boat.

The angle of that clew line, when reefed, is a related issue. When a mainsail is reefed, it essentially becomes a loose-footed sail (even if the actual foot of the sail is slotted into the boom). A reefed sail’s draft and twist control is not unlike a headsail’s; in other words, the angle of the jib or genoa sheet and the angle of the clew reefing lines determine the sail’s twist, while the tension on these respective lines controls the draft. So it is vital that the position of the clew reefing hardware is correct, and this is easily determined.

With your mainsail lowered to its reefed position and the new tack placed into its reef hook (or, similarly, with the tack reefing line taut and made fast), pull on the clew reefing lines and manually change their angle. When you pull downward, hard, the sail’s leech tightens and its twist is reduced, while the foot of the sail loosens and develops more draft. Likewise, when you yank the clew reef line upward, the foot of the sail becomes tighter and flatter, while the leech loosens and develops more twist.

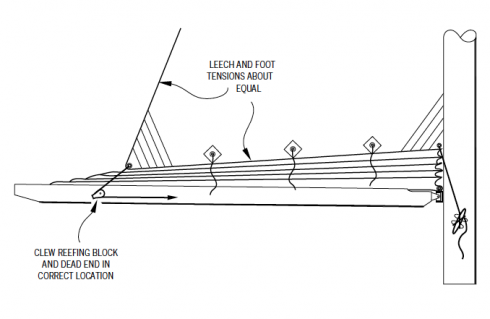

Ideally, you want to strike a balance so the leech and foot tensions are about the same. The angle for this clew reef line might not be perfect for all points of sail, but you will need to reef most often when sailing to weather, so I recommend adjusting the clew hardware accordingly.

Many older boats have the cheek block for the reefing clew on a track so small adjustments can be made to accommodate changing wind velocities and points of sail. If you want to split hairs, a block on a track is the way to go. Clew reefing hardware at the end of the boom will never result in a reefed sail that is well-trimmed.

Tacks and Leeches

When reefing a mainsail, the first reef-point connection to make is the tack cringle. But this can be difficult if the sailmaker has not made adequate accommodation for the stacked-up luff on the mast that occurs when lowering the sail.

If you are using reefing tack hooks, a major problem can occur if there is a slug-entry closure in the mast that prevents the luff from dropping fully to the gooseneck. A ring pendant may be added to the reefing tack cringle so the tack hook can be reached. Cringles for second or third reefs will also require pendant extensions.

If your mainsail is set up with reefing tack lines, rather than gooseneck hooks, the problem of sail stacking is greatly reduced. But the height of the reefed tack position still causes distortion with the sail. My recommendation is to close the slug entry with a semipermanent cover that will allow the sail stack to be much lower. If using tack reef hooks, you’ll still use extension pendants, but that stack will be much shorter.

Along the trailing edge of the main, chances are that your sail has a small-diameter leech line that begins at the head of the sail and extends all the way to the foot. The leech line exits the leech hem through small cringles just above the boom and at the respective patches for each reefing clew. A small cleat will be situated at each reef point. Once a reef is tied in, you should apply just enough tension on the leech line to stop any flapping or movement of the sail’s leech, and then make it fast. When shaking out a reef and before you fully hoist the main, always remember to slack those leech lines to prevent a series of distinct hooks in the sail. Not only do they look bad, they’re also inefficient.

Boatbuilder, naval architect, author, illustrator, marine surveyor and long-time CW *contributor Bruce Bingham is also the proprietor of Bruce Does Boatwork, a yacht repair and refit business in St. Petersburg, Florida. *

Comments